West of Penance

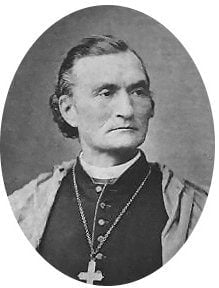

Archbishop Lamy’s story inspired me to write West of Penance

Archbishop Lamy

A few years ago, I heard a startling true tale of old New Mexico from a friend of mine, Monsignor Jerome Martinez y Alire. He said that the newly appointed bishop of the diocese of Santa Fe, Jean-Baptiste Lamy, didn’t care for the small adobe church in the center of Santa Fe when he arrived there in 1851. He envisioned a large cathedral, like those in his native France, to serve as the mother church of this southwest archdiocese that covered an area roughly the size of present day New Mexico, Arizona, and part of southern Utah. It had taken Lamy nearly twenty years to raise the funds to begin construction. But cost overruns and delays constantly plagued him.

Click for More about West of Penance

He received donations from various sources. Jewish businessmen like Abraham Staab and the Spiegelberg Brothers, attorney Thomas Catron, and others made generous contributions to the cathedral fund. And Lamy did not discriminate when it came to accepting money. Maria Gertrudis Barceló, better known as Doña Tules, proprietress of a “comfort station” in Santa Fe, providing arguably the finest gambling and prostitution services around, donated $1,000 to the building effort, a tidy sum then. (She is buried under the south transept of the cathedral.) But still Lamy needed more money. He had even sold his carriage to help pay construction costs. By 1875, with his cathedral only partially completed, Lamy, now an archbishop, set out on horseback across the archdiocese to ask for loans from his parish priests. (Many of them he had recruited from trips he’d made back to France.) Stopping in the village of Mora, Lamy told the young priest there, Father Garassu, he would repay with interest any money the priest could loan him. Father Garassu said his parish was poor and in desperate condition. Lamy was about to leave when the father asked Lamy how much money he had already gathered. Lamy said he only had a few dollars. Father Garassu asked the archbishop if he would trust him with those dollars and remain there and take care of his parish for a few days. “And if I return with any money,” the priest said, “you must not ask me how I came by it.” Lamy agreed. Father Garassu kissed the archbishop’s ring, saddled his horse and rode away. Returning a few days later, the good father handed Lamy a sack filled with coins and greenbacks. About two thousand dollars worth. Astonished, Lamy thanked him and asked how he had gotten the money. Father Garassu reminded him of his promise not to ask. Grateful, Lamy departed. About ten years passed. Lamy was now old and ill. Priests from across the archdiocese came to pay their respects. When Father Garassu sat by his bed, Lamy recalled his promise not to ask how the priest had come by all that money, but he hoped he would tell him now. Father Garassu said that before he joined the priesthood he had been in the French Army, and had learned many ways of the world. One of those was how to gamble. He told Lamy he had taken his few dollars and ridden to Fort Union some thirty miles away. The officers there had invited him to play cards on previous occasions and he’d always declined, but not this time. It was payday and the good father had cleaned them out. What a great story, I thought. And then I wondered, what if Father Garassu had been robbed on his way back to his parish?

As Featured On True West Magazine

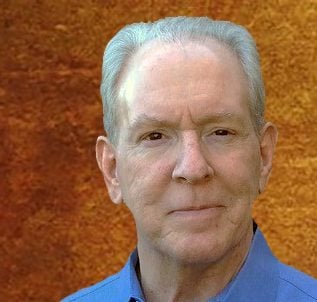

Tom has always had a love of the West, of film and of writing. Born and raised in San Diego, California, he attended the University of Southern California. He spent more than twenty years in Hollywood working as an assistant film editor, as well as freelance writing. Devoting himself to writing historical fiction full-time, he and his wife Marilyn moved to Santa Fe, New Mexico, where they adopted their cat, Cody, whom they are home schooling with great success.

Tom has always had a love of the West, of film and of writing. Born and raised in San Diego, California, he attended the University of Southern California. He spent more than twenty years in Hollywood working as an assistant film editor, as well as freelance writing. Devoting himself to writing historical fiction full-time, he and his wife Marilyn moved to Santa Fe, New Mexico, where they adopted their cat, Cody, whom they are home schooling with great success.